Man at Work

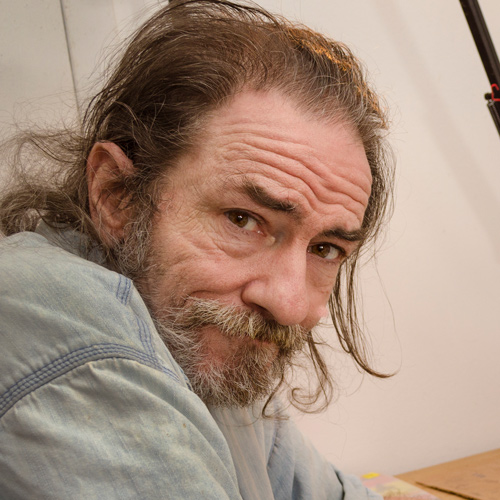

Ralph is going to work. He stands from the couch and slowly uncurls several feet of hose from the oxygen tank Ralph has with him at all times. Ralph is a client at H.E.A.R.T. Services, which promotes independence by providing support to individuals in recovery who are aging and medically fragile.

Ralph has Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and can’t go far without a steady and constant flow from the oxygen tank. But he needs to work every day. So RHD’s Environmental Design team made sure he had a workspace that fit him, and each day Ralph makes his way into his workroom to produce intricate models and miniatures with a life all their own.

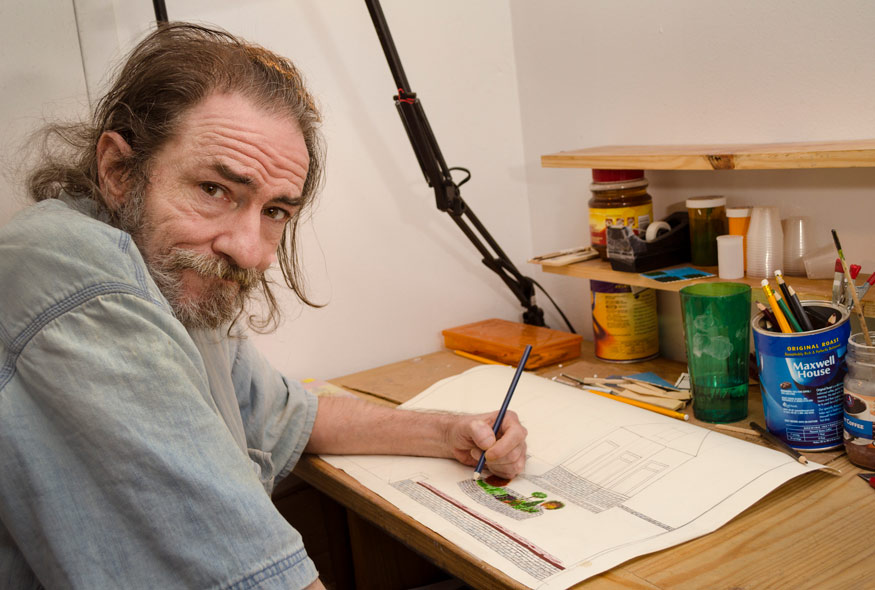

“Here’s where I live; there’s where I work,” Ralph said, gesturing at the living room of his apartment and then pointing toward the back where his assorted materials are stacked on his desk.

“I don’t know what he’d do if he couldn’t work,” said Collin Mullins, a clinical manager who works with Ralph. “If he can’t work, his anxiety level is really high, which sometimes results in hospitalizations. But working calms him and focuses him. He feels much better if he can work.”

Ralph is a carpenter with experience in construction. His physical and mental health issues make working in traditional settings impossible; he often can’t leave his apartment. But he’ll see something outside the window of his West Philadelphia apartment, or come across a structure in a magazine or online and he’ll be moved to re-create it in his workshop.

“I’m still learning myself why I do it,” he said, as his fingers worked over the roof of a miniature gazebo he’s working on. “Someone said to me, oh, you’re an artist. Well, I don’t consider myself an artist. I don’t think of myself that way.

“I just don’t know what I would do with myself if I didn’t have this.”

He scavenges materials wherever he can; discarded wood, spare parts, items donated from friends or RHD staffers. When he can, he’ll purchase materials from local art stores.

From a picture in a magazine, or an image he finds online, or a memory in his head, Ralph will create stunningly lifelike miniature models. He creates a house, perfectly to scale, with working windows and doors and a painstakingly crafted fireplace. His gazebos, and he will produce several in succession, are exact down to the smallest detail — even the rafters of the gazebo’s roof.

But a living space that fit his work needs was a particular challenge. RHD’s Environmental Design team visited his home and quickly set about working with Ralph to build something that would suit him.

“He had this tiny desk in a room he was sharing with another client,” said Barbara Hammer, RHD property acquisition coordinator. “His bed, his dresser, every piece of every surface was covered with whatever he was working on. It was very disorganized — although he seemed to know exactly where everything was.

“The best we could do at that time was get shelves up for him. But then he moved into a new apartment where he had his own living space, and we thought we could put something nice together for him and make him a real work area.”

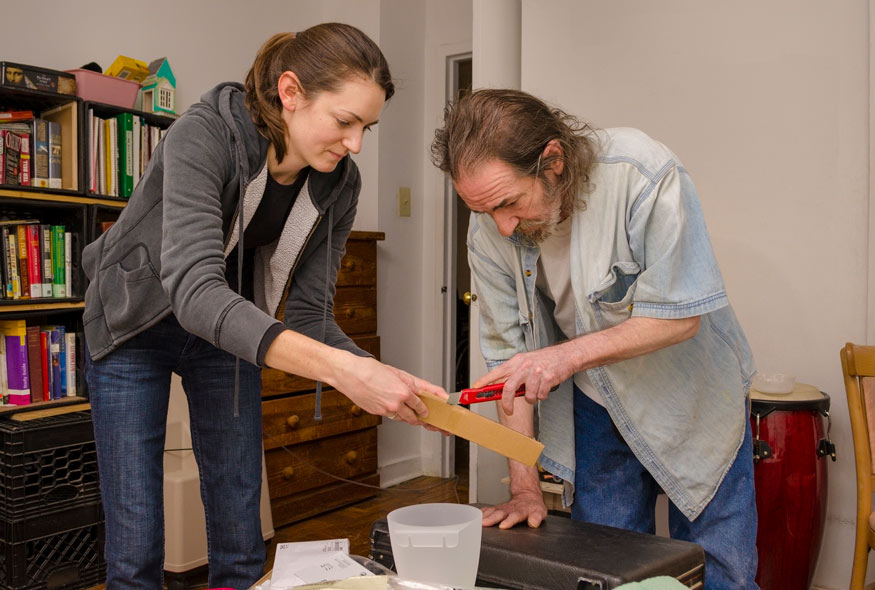

Hammer and Leah Forrest, RHD corporate program coordinator, always work with the clients to create an environment that reflects their interests and needs. The effort underlines RHD’s value of person-centered services, creating a place that meets the clients’ needs and enhances quality of life. By engaging the clients and supporting them as a vital part of the process, clients take pride in their living spaces, their belongings and themselves.

But Ralph, with his background and experience, presented a unique challenge.

“We had a little bit of negotiation,” Mullins said, laughing.

“He had strong opinions on what he wanted; where he wanted to sit, where he wanted things to go,” Hammer said. “There was a tremendous amount of discussion and negotiation, and we each had to compromise on some things. He’d drawn up plans and shared his drawings, and we had to get his blessing to make changes. He’s got some experience, he knew what he was doing, and I wanted to honor that. He had definite ideas about what everything should look like, and I wanted to be very careful to respect his wishes and his knowledge.

“I was having a tough time drilling into one piece of the wall, the screws wouldn’t hold, and he took one look and said: The studs are metal. And I thought, well, how would he know? But sure enough, they were metal.”

In the end, Ralph liked his workspace, and spends hours on his projects.

“I can’t think of anyone like Ralph; the way he replicates stuff that he sees, the way he can take what’s in his head and make it,” Hammer said. “I was blown away by his work.”

Ralph offers his designs for sale, but he usually gives his designs away as gifts.

“Well, I like for people to see it,” he said. “I like to get eyes on it. I’m glad that people like it when they see it. I used to take on jobs where I’d, say, re-do somebody’s kitchen. And the look on their faces when it’s done, when they see this new thing they have and give you that big smile, that was the whole thing, for me. That’s what made me feel good.

“Having this space is nice, but it’s not about me — it’s about the work I can do. I put my heart and soul into my work. I do one thing at a time, and I put my heart and soul into each piece.”