By the book

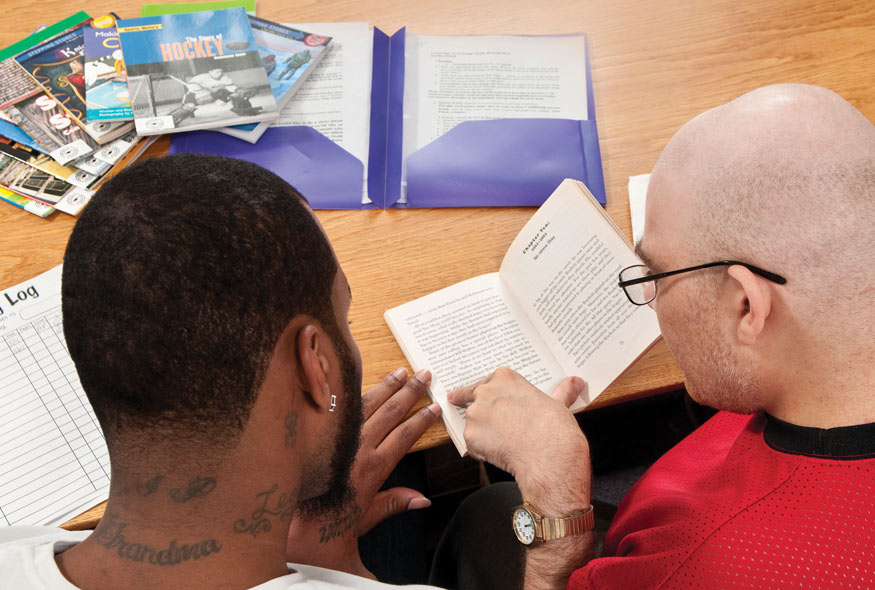

Chris traces his finger across the page, reading aloud, and comes to a wrenching halt. His brow furrows and he strains with the effort, and finally says: “Un … un … unaccustomed.”

“Good job,’’ says Dennis Jones, his reading coach.

Then, a line later, Chris stumbles again. “I don’t know it,’’ he says. Spell it, Jones tells him, and Chris spells it. Sound it out, Jones says, and Chris breaks down each syllable until he finally puts it together: “Intelligence.”

“Good job,’’ Jones says, and Chris smiles.

Chris, a young man with intellectual disabilities, is just one of an extraordinary group of people who gather each week to do something teachers and counselors told many of them they would never be able to do: They are learning to read.

Every Tuesday at RHD’s corporate headquarters in Philadelphia, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities – including traumatic brain injury – are learning to read, or improving their reading skills, in a fascinating new program developed by RHD occupational therapist Christine Silverman and put into action by staffers at local RHD programs.

“It is a basic human right to be able to read,’’ Silverman said. “People deserve the opportunity to try. It’s what’s right, it’s what should happen. So how do we make it so it can happen, so that everybody can do as much as they possibly can? We’re not talking about reading astrophysics tomorrow. But can you read at a higher level? Yes.

“I believe people can. If it’s structured in the right way, it you provide the right kind of support, people can.”

RHD’s programs for people with intellectual disabilities include an individualized support plan, in which residents identify a life plan and set goals they want to accomplish. Some are big, some are small. Almost without exception, they reported that what they really wanted to do was learn to read.

“It jumped right out,’’ Silverman said. “Some guys wanted to get their GED. Some wanted to complete high school. Some wanted to learn to cook, and needed to be able to read a recipe.

“We did a lot of investigation into literacy programs that were out there already. They were geared for people without disabilities, or with minor disabilities. There just aren’t many programs coordinated to support individuals with this type of need, and with these cognitive issues.”

So Silverman collaborated with an educator who had developed a reading program for students for whom English is a second language. It was hybridized from four different models, once of which included a 1:1 coaching component to make sure the students had individualized attention and support.

“You can’t help but succeed, because it’s based on what the individual is able to do,’’ Silverman said. “It meets them where they are.”

Individuals read from a selection of books at their particular level. As they get stronger and build skills, they move to the next level. It’s a success-based model, in which everything from language to tone of voice is positively structured. They never hear: “no, that’s wrong.”

A dedicated group of RHD staffers works tirelessly with the readers. Silverman calls them “coaches.”

“People who have challenges get told all the time what they can’t do,’’ said Josh Gutierrez, an RHD therapeutic residential specialist and a reading coach in the program. “When you give them a chance to see what they can do, a whole new world opens up to them.”

Jerry is an RHD client with traumatic brain injury, and people told him for years learning to read was an impossibility. Yet here he is every Tuesday, reading.

“They look forward to it, every week,’’ Jones said. “This isn’t something where we have to get them ready, and make sure they’re here. Before we have to leave to get there, they’re assembled and ready to go. They’re always excited about it.

“One of the nice things we do is hand out awards to students. Christine gave them a gold medal. (Dan) wears it around his neck all the time. He’s proud of it, and he should be.”

Students who arrive for the reading group chatter happily as they find their materials, line up their rooms and begin reading.

“Every single student has moved up,” Silverman said. “People feel good about themselves because they’ve shown improvement. They have tangible proof that they’ve achieved something, they’ve grown. Those kinds of positive changes in self-esteem are invaluable.”

Gutierrez and all the reading coaches get training on how to support the consumers, and administer assessments to determine when they’re ready to move up to the next level. Gutierrez works with David, who regularly asks him if he’s ready to move to the next level. David races through the book in front of him, but still struggles occasionally over a word.

“Slow down,’’ Gutierrez said. “One letter at a time.”

“Everybody,’’ David said. Gutierrez tells him to use it in a sentence.

David frowned and thought, and then he smiled as he hit upon the perfect sentence: “Everybody … can learn to read.”